Peggy Whiteneck, Freelance Writer |

|||

Have We Always Been the Disunited States of America?The fabric-tearing, gut-wrenching divisions between citizens in this era of Trump are not new. They didn't originate in the Civil Rights or Anti-War movements of the 20th century, nor are they rooted in the Civil War of the 19th century. Ever since the Revolution itself, the "United States" has been more an aspiration than any solid reality. Throughout our history, we have so much been at each others' throats that the miracle is we've survived at all as a country for more than 200 years. Still, our survival for 200 more is by no means assured, and if the center can't hold, it will be because of homegrown, violent impulses nurtured within the bosom of America itself. It won't be because Middle Eastern terrorists hate us. It will be because we hate us. For a long time now, I have intuitively felt this, though I have kept it to myself and tried to sublimate it as best I could - that the national center doesn't really hold, that we are too disparate in the many states that make up our States, too little held together by shared values. And I have wondered what will become of us as a country. It's not that I reject the aspirations contained in the patriotic tropes and symbols of my childhood. It's just that the price of growing up has been that I don't believe them anymore. This intuition blossomed into a revelation after I watched a film called The Free State

of Jones. It's a fictional account of an actual historical event: a rebellion within

Mississippi in which Southern citizens actively fought against the Confederacy. Having

never heard such a tale in any history course I'd ever taken, I was fascinated

by it. I discovered the film was based on a non-fiction book, The Free State of Jones:

Mississippi's Longest Civil War, written by Professor Emeritus of history at Texas

State University, Victoria E. Bynum. So I read the book.

This is not a book written by some partisan hack with an axe to grind. It's heavily researched and documented; in fact, the last third of the book consists of footnotes for the chapters and an extensive bibliography. Some of these sources are the records of people who lived during the Civil War and actually knew the Jones County band or were members or descendents of it. It is not surprising that these sources differ markedly in what they consider to be the facts, let alone their own interpretations of those facts. Bynum, to her credit, does not try to reconcile the discrepancies but merely points them out as illustrations of the book's underlying themes of dueling American mythologies and a disharmonic American story. What They Don't Tell You in SchoolBynum traces the roots of Jones County's "civil war within the Civil War" to the

stresses and strains, tracing back to the birth of the nation in the late 18th century,

of trying to form a country out of disparate elements. These tensions would grow as the

income and wealth gap (sound familiar?) grew between subsistence farmers who were just

trying to get by and a slave-owning planter class that was amassing all of society's goodies

from land to money. By well before the Civil War, at least some non-slave-owning white

families had begun to feel that they shared far more in common with Black folks than they

did with white planters. And, as Bynum points out late in her book, it wasn't just in

Mississippi that these intra-Confederate rifts were happening but in small pockets of

resistance throughout the South.

Zooming out from Mississippi, the challenges of keeping the nation together were exacerbated by the sheer size of the country being created by westward expansion, pioneered primarily by poor white farmers wanting to escape the meddlesome interference of the planter and commercial class and its clergy. Westward pioneers created a new set of national tensions and ill will by planting their homesteads on lands pillaged from indigenous Native Americans. (Today, it amazes me how many people, in differentiating themselves from "immigrants," refer to themselves as "native Americans" when almost none of them are.) In the midst of class tensions among whites, the objections of Indians to the subversion of their way of life, and the growing aspirations for freedom and dignity within Black people both enslaved and free, one of the main pot stirrers was evangelical Christianity (again, sound familiar?) - and we're not talking here about the right side of history. Then as now, evangelical churches were more concerned about who was not going to church and who was dancing and drinking and gambling and shacking up with whom and "taking the Lord's name in vain" than they were with larger moral issues touching on racial justice and a definition of the "common good" that excludes all the have-nots. In fact, evangelical churches subscribed then - as many of them still do - to a deeply ingrained belief that if people are rich, it's because they have earned God's favor. As a corollary, poverty is God's judgment on a sinful life. The genteel lifestyle cultivated by the planter and wealthy commercial classes was thus considered by the churches of the antebellum South not only as a sign of God's favor but also as an important control on the rougher elements of society - particularly those who would not kowtow to church doctrine and rules. The churches also served as the arm of social order on what was then the South's western frontier. As such, the churches placed a high premium on white men's subservience to the church and on women and Black folks being subservient in turn to white men. Consequently and with few exceptions, Southern evangelical churches supported secession, the Confederacy, and slavery itself as the South's peculiar but righteous institution. The Truth of Tara

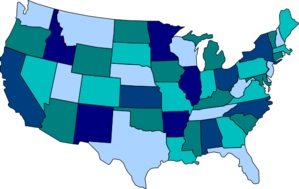

Bynum's book debunks the mythology of "The Lost [and Noble] Cause" that seeks to present alternative motives for the Civil War such as arguments over states' rights and claims of "Northern aggression" and/or that tries to paint plantation life as if slaves were happily singing in their chains. She makes the case that the War was every bit about slavery because slavery was what built and sustained the lifestyle of the planter class that called all the shots in Southern states. The Civil War was about maintaining the social prerogatives of the ruling planter class - and about keeping everyone else in their place. It's important here to avoid, as Bynum is careful to do, drawing rigid lines between Southerners who were committed to the Confederate cause and those who actively fought against it. So strong was the societal bias in favor of wealth as a sign of social worth that any yeoman farmer who could aspire at all to some degree of gentility worked hard to achieve it. One of the signs of rising status was owning slaves. Thus, any farmer who could afford to do so bought at least one. Still, this left many subsistence farmers who never owned slaves, whether because they couldn't afford to or because they objected to slavery on principle. And it was this considerable group on non-slaveowners that would rebel in its turn against the Confederacy. The Jones County band was composed of a few conscientious objectors, but in much greater numbers by deserters, who, finding "gory" rather than "glory" on Civil War battlefields, began first to wonder what the hell they were fighting for and then to reach a conclusion so commonly shared among them as to become a shared slogan: The Civil War, they said, was "a rich man's war and a poor man's fight." This slogan was glaringly illustrated by the fact that any white man rich enough to own 20 or more slaves was exempt from military service in the Confederacy. Same Old Same OldAfter the war, the Jones band, having already committed the unforgiveable sin of siding with the Union, further aggravated the sensibilities of the good white people of Mississippi by a casual attitude toward inter-racial relationships and as close to gender equality as those times would ever get. These unbreakable social bonds within "the Free State of Jones" and the racially mixed offspring that resulted from them infuriated a white supremacy dedicated to strict racial segregation and the principle that people of color must be sufficiently and publicly identified as such as to be able to isolate them from the privileges and prerogatives of whiteness. The "new slavery" of segregation and Jim Crow was the workaround white supremacy created in the immediate aftermath of the South's defeat in the war. It would serve as a remarkably resilient workaround over the next hundred years. Even while the toxic vestiges of both segregation and Jim Crow persist in many parts of the country, there is today also a direct line from the institution of slavery to the disproportionate incarceration of people of color for crimes their white counterparts may commit with impunity and to the disproportionate representation of young African-American men among the corpses left behind from cop shootings. In our so-called "classless society," we are driven and riven by class. We are

ways-parted by religion, dissected and transected by gender. We are segregated by

fantasies about race and what it means. We view each other across

a grand canyon dividing political enclaves. Individual states within the 50 might just

as well be their own countries so diverse are their cultures, their demographics, and

their approaches to social problems and so hostile are they to other states not like theirs.

The most accurate and descriptive name for the conflict commonly called "The Civil

War" is "The War Between the States."

So, no, Trump's fractious America is not new. We have been here before. After all, working class and poor whites know very well they cannot go up against the real powers that be - however corrupt and exploitative those may be - and win. Beating up an immigrant or harassing an African-American minding his own business is an outlet for the otherwise impotent rage of disaffected whites. Nor, as we saw in the attack on Republican lawmakers just prior to the annual Congressional baseball game in June 2017, do so-called "liberals" feel any less impotent nor exempt from their own murderous rage against the machine. In the United States that has always been, episodic blood lust can easily devolve into the kind of fratricidal conflict that gave us the Civil War - a conflict from which, even to now, neither side has ever fully recovered. We can't ensure the survival of the nation by homogenizing it as we have historically tried to do so that the default citizen is an affluent white male. That attempt to make us all fit the same template with only minor variation is the original American sin that threatens our survival, and we are still committing it: Native Americans and immigrants both must talk and act as if they were white Anglo-Europeans; women must know and embrace their "place" as subservient to men and stop trying to compete with them in the workplace; children must be out of sight and out of mind so that we don't have to think about how our political decisions about taxes and health care and immigration affect them; people of color can’t be white though they should aspire to get as close to white as possible without encroaching on the prerogatives of whiteness; poor people must get right with God so they can get their heads above the poverty line; America's preferred religion is Christianity and adherents of other faith tradition are condemned by God. This war on heterogeneity that seeks to make us all one by making us all toe the same cultural line is, as the Jones band came deeply to understand, a fool's project. It is a rich white man's war that the rest of us are expected to fight. Where Is the Way Forward?

The alternative to this bogus unity is for us to recognize the only legitimate basis for what has been described as "American exceptionalism." America is not exceptional because it is always right, for the history books, at least those that refuse to engage in patriotic propaganda, are too well-stacked against that myth. Nor is America exceptional because we've convinced ourselves that we always win in war even when we don't. It's not even exceptional because of our system of government, flawed as it is. It is not exceptional because it follows the rule of law since we too often don't. It isn’t exceptional because it rejects the use of torture, as we routinely practice it not only in our treatment of terror suspects but within our own prisons, nor because we are a beacon of human rights as we violate them and support overseas regimes that also violate them. America is not exceptional because Donald Trump's "great again" chant, based as it is on selective memory, has any basis in historical reality. The basis of American exceptionalism is this and only this: that the various states in a land this large and diverse could nevertheless cleave together as a one nation. That is the new-old center we must find, the only center that will hold. More Peg's Blog Spot Posts· The Unacceptable Cost of Deferred Maintenance· American Voters and the Cult of Celebrity · We Have Met the Enemy and the Enemy Is Us · Wanted: A Working Government · The National Divide: Immediate Gratification vs. Future Gain · The Trouble with That Anonymous Trump-Circle Editorial · What "Telling It Like It Is" Really Means · Breaking News: We're All "Values Voters!" · Monuments Flap Is Not about the Monuments · A Humble Defense of the Constitution · The Trump Presidency: Bigotry's Cause or Only Its Effect? · Race, Class, and Access to Women's Health Services · Trump's Angry White Folks · Whatever Happened to "Look It Up?"

The logo banner for this site was generated at Cool Archive (http://www.coolarchive.com/) and the side border graphic was provided courtesy of Pambytes (www.pambytes.com). Special thanks to the late Monica L. Stewart for the matching logo design. Buttons at the bottom of the page were texted using graphics provided courtesy of Button Generator (www.buttongenerator.com). All photographs and text content on this site are © Peggy Whiteneck. No reproduction of any part of this content is permitted without express permission of the web site author. |